The battle for Armani: Who will take over the designer’s empire?

Giorgio Armani’s will outlined hopes for one of three European giants to buy into his fashion group. But a deal may prove complex.

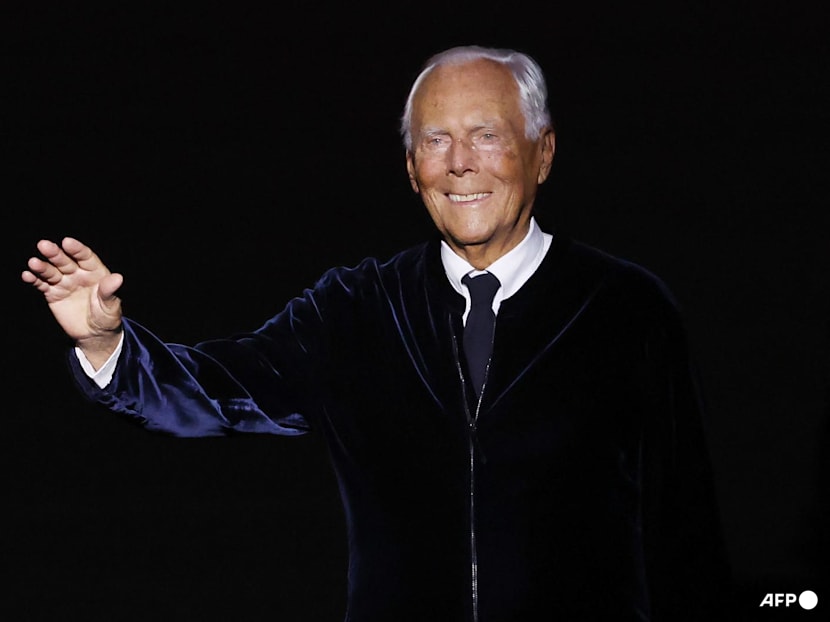

Italian designer Giorgio Armani greets the audience during his Giorgio Armani Prive show during the Women's Haute-Couture Spring/Summer 2024 Fashion Week in Paris on Jan 23, 2024. Italian fashion great Giorgio Armani has died at the age of 91 "surrounded by his loved ones", his company said on Sep 4, 2025. (Photo: Emmanuel Dunand/AFP)

Giorgio Armani repeatedly vowed he would never sell his eponymous Italian fashion empire to a French conglomerate, and in 2016 the designer even went as far as establishing a foundation to shield it from break-ups or takeovers.

Yet in advance of his passing this month, aged 91, Armani’s resistance had melted away.

In his will, drafted in March and published on Friday (Sep 12), Armani tasked the Giorgio Armani Foundation with selling a stake in the company he started in Milan 50 years ago.

Many in the Italian fashion industry were shocked to learn that two of his three preferred suitors — LVMH, L’Oreal and EssilorLuxottica — are French and that Bernard Arnault, the French billionaire who controls LVMH, had the opportunity to pounce on a coveted Italian asset.

Armani’s will has fired the starting gun on a potentially extraordinary battle to buy into a fashion institution, which analysts estimate could be worth at least €7 billion (US$8.3 billion; S$10.6 billion).

Getting hold of a piece of Armani — one of the world’s largest privately owned luxury groups — has long been regarded as a major prize in an industry with a limited number of viable targets.

Friday’s announcement was met with effusive responses from Armani’s anointed suitors.

Cosmetics giant L’Oreal, which has produced Armani’s popular beauty line for almost 40 years, said it was “touched and honoured” to be considered. Meanwhile, EssilorLuxottica, the Milan-based eyewear group which plans to move its global headquarters to Paris, said it was “proud” to be named and would carefully consider the opportunity.

Yet insiders at both companies cautioned that despite those warm words they were unlikely to attempt to buy Armani outright.

For LVMH, the luxury industry’s dominant force, it’s a different story. Industry executives in Milan and Paris told the Financial Times that Armani could be a welcome addition to Arnault’s vast stable of brands. The French magnate has had an eye on Armani for some time, according to people close to LVMH, and would take an interest.

Arnault said he was “honoured” his company was named as a potential partner by the late designer and drew parallels to the talent of Dior founder Christian Dior.

“If we were to work together in the future, LVMH would be committed to further strengthening [Armani’s] presence and leadership around the world,” Arnault said.

Three luxury executives in Milan expressed surprise that Armani had mentioned LVMH in his will.

One person mentioned the 2023 documentary Milano. The Inside Story of Italian Fashion, which features Armani ruling out a sale of his group to the French. “It’s just unthinkable that only a few years later, out of all people he mentioned Arnault as his preferred buyer,” the person said.

Armani’s will also instructs his heirs, which include right-hand man Leo Dell’Orco and members of his family, to consider other groups “of the same standing” as potential buyers, and to prioritise those that already “entertain partnerships” with the fashion house.

An initial 15 per cent stake is to be sold within 18 months from his death, with an additional 30-54.9 per cent going to the same buyer in three to five years, according to a copy of the will obtained by the Financial Times (FT).

According to the will the Giorgio Armani Foundation — in which Dell’Orco, nieces Roberta and Silvana, nephew Andrea Camerana and sister Rosanna own stakes — will always own at least 30 per cent of the group.

For those who wish to own the rest, Armani’s lucrative licenses, particularly its highly successful beauty deal with L’Oréal, are likely to be attractive assets.

The Armani Prive fragrance line, launched in 2004, retails for about €300 a bottle. Meanwhile, Acqua di Gio, which has been on the market since 1996, is one of the best-selling men’s perfumes of all time.

But with the beauty licensing deal with L’Oreal set to run until 2050, potential buyers are unlikely to be able to capture all of the value.

The breadth of Armani’s product range — which spans its EA7 sportswear line, through to its accessible casual wear label Armani Exchange and the high-end Armani Privé line — may also act as a deterrent to buyers.

Some luxury executives believe the variety of products bearing the Armani name serves to dilute the brand and confuse consumers. As well as beauty and fashion, the Armani group owns restaurants, hotels and a high-end home design line.

Pierre Mallevays, co-head of merchant banking at Stanhope Capital, said a standalone Armani group “works very well, but it’s hard to see a big strategic buyer being genuinely interested in all of its operations”.

While LVMH is viewed in the luxury industry as the most likely buyer, the group’s upmarket positioning implies it will have little interest in the more affordable lines in the Armani stable, which contribute a significant portion of its €2.4 billion annual revenue.

LVMH also tightly controls product distribution to enable it to charge higher prices, while Armani products, which are distributed through wholesalers, are often discounted.

One leading Italian executive said it was hard for any strategic investor to buy an asset and “sit on it” for a while before “deciding what to do with its various parts in the longer term”.

“That’s what the prospect of buying Armani would look like,” they said.

In his will Armani raised the possibility of a public listing of the business if plans to sell a stake failed. That would see Armani follow in the footsteps of other Italian family-owned fashion brands, such as Prada, Cucinelli and Moncler, which have gone on to list on the public markets. In each case the brand’s family owners have retained a controlling stake.

In several interviews with the FT, the late designer, who led his company until his passing this month, said his priority was to protect his legacy.

Armani’s executive committee said in a statement after the will was made public that the foundation would act “as a permanent guarantor of compliance with the founding principles”.

Two industry executives said Armani might have named LVMH, L’Oreal and EssilorLuxottica because they have the scale and financial clout to secure the group’s future and his legacy.

Armani’s desire to sell a stake to a larger group makes sense, according to Bernstein analyst Luca Solca, because there is a “lot of work to be done to ensure the continuation of the Armani brand legacy”.

“[Armani] liked to run his own business and there is an element of vanity when you are a very, very important designer — you don’t want to be part of a much bigger group. [But] today we are seeing a more rational side”.

Silvia Sciorilli Borrelli & Adrienne Klasa © 2025 The Financial Times Ltd.

This article originally appeared in The Financial Times